Ask good questions in order to address your information or research needs.

If you have no question, if you don't wonder about something, then you have no need to find anything out.

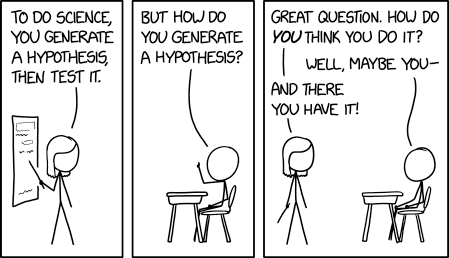

All search and research starts with a good question. Good research questions may start with seeking a "yes" or "no", but good scholarship often concentrates on the "why" and the "how". I think this happens because.... a hypothesis.

Then you seek out information to provide good evidence to answer it.

Self reflection: When was the last time you asked "Why"? (or What or How)?

All humans can do science (scholarship), by asking questions and trying to answer them. If we relax, we can just start to generate hypotheses and then seek out evidence (do research) to test and see if the hypothesis works.

XKCD 2569 cc-by-nc 2.5

This video shows you how mind mapping helps you turn a broad topic into a good research question.

Generative AI tools can also help you to create mind map.

GitMind is a free web-based diagramming application that enables you to create a range of diagrams, including mind maps and flowcharts. With its AI-powered mind-mapping feature, GitMind can help you generate and visualize ideas. Below are the steps:

Remember that the information you find on Generative AI might not always be reliable, so you should check & cross-check the results.

A topic is NOT a research question.

A question is more specific.

Example: What is the Grass?

Possible Questions that might lead into different research areas:

Suggestions

1. Do some background reading, and/or outline what you have learned about your topic from previous classes and reading in the past few years

2. List questions & answers you may already have, along these lines

3. Think about your questions and what answers you have.

4. Try to make a few clear questions, that are based on some of the ideas (theories, words, methods) that you have learned in your course.

5. Try to choose one of the questions, not too wide & not too narrow.

6. Be prepared for your question to change.

Based on: "How do I get from a topic to a research question" - from Cambridge LibAnswers

This section is based on The Craft of Research, with examples added by HKUST librarians.

3.1 From an interest to a topic: start with what interests YOU. Then ask yourself, what interests me about it? What would interest other people?

In the Library, look up background information to see if the topic is viable (for example by searching Britannica Academic for the terms bamboo and grass) and to explore the internet carefully by googling bamboo and grass. or Perplexity, asking "what is the grass" or searching "bamboo and grass".

If you're at a more advanced stage, start looking for books, book chapters, or articles in trade magazines and scholarly journals om PowerSearch or disciplinary databases (Business, Engineering, Humanities & Social Sciences, Law, Medicine, Science & Math).

3.2 From a Broad Topic to a Narrow One: Try to use action words to make your topic dynamic.

Example: "Bamboo in world trade"; or "bamboo as a carbon sink"; or "the physics of bamboo structures in high winds"; or "bamboo symbolism in contemporary Chinese art" are static.

Try to restate your topic as a sentence, it may bring your topic closer to something you could try to prove (a "claim").

A child said What is the grass? fetching it to me with full hands;,

How could I answer the child? I do not know what it is any more than he.

I guess it must be the flag of my disposition, out of hopeful green

stuff woven.

Or I guess it is the handkerchief of the Lord,

A scented gift and remembrancer designedly dropt,

Bearing the owner’s name someway in the corners, that we may see

and remark, and say Whose?

Or I guess the grass is itself a child, the produced babe of the vegetation.

Or I guess it is a uniform hieroglyphic,

And it means, Sprouting alike in broad zones and narrow zones,

Growing among black folks as among white,

Kanuck, Tuckahoe, Congressman, Cuff, I give them the same, I

receive them the same.

And now it seems to me the beautiful uncut hair of graves.

- Walt Whitman Leaves of Grass Book II, 6.

Before you start searching for information (whether via Google or Library databases), you should clarify "what do I really need to find?" or "what will satisfy my need for information?". Ask yourself these questions:

If you are not sure about any of the above requirements, talk to your instructor.

Once you have a clear picture of what you need, you can then examine your assignment topic, break it down into small components (concepts and keywords) to make your search more efficient.

Read your research assignment or question carefully.

"Knowledge pursues truth, and the crisis of science today is caused, at least partially, by the fact that scientists since the beginning of the modern age, have had to be content with provisional verities which will be challenged tomorrow. Philosophy asks the unanswerable questions of what does it mean that everything is at it is, or why is there anything and not rather nothing, and the many variations of these questions. By distinguishing between thinking and knowing, I do not wish to deny that thinking's quest for meaning and sciences' quest for truth are interconnected.

By asking the unanswerable questions of meaning, people* establish themselves as questions-asking beings. Behind all cognitive questions for which people find answers lurk the unanswerable one which seem entirely idle and have always been denounced as such.

I believe that it is very likely that people, if they should ever lose their ability to wonder and thus cease to ask unanswerable questions, also will lose the faculty of asking the answerable questions upon which every civilization is founded.

In this sense, the need to reason is the a priori condition of the intellect and of cognition. It is the breath of life whose presence, psych-like, is noticed only after it has left its natural abode, the dead body of a civilization which is no more."

- Hannah Arendt (1973). Address to the Advisory Council on Philosophy at Princeton University. In: Thinking without a Banister: Essays in Understanding, 1953-1975. Jerome Kohn (ed.). New York: Schoken books, 2018, p.488.

* Minor edits to make these passages gender neutral

Please watch the following 1-minute video that explains how brief background research can be used to help you:

Additional viewing options: Turn on closed captions with the "CC" button, or use the text transcript

Links to an external site. if you prefer to read.

As noted in the video, background information is often most effectively found in sources that provide a broad overview of the topic, such as encyclopedias. In the library world, we call these "reference sources."

The library has many reference sources, both in print (at the library), and online (via the library databases).

Links to an external site. is an excellent resource for background information, and you are encouraged to use it as a starting point for your research. Tip: Use the "Contents" box available for most articles to scan for potentially relevant and interesting sub-topics.

Citations & Attributions

"Background Research " by Steely Library NKU

is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0

Links to an external site." by Nohat for Wikimedia Foundation Links to an external site. is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0

cc-by from Cabrillo College

Research can be seen as a form of Inquiry - Questioning

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial Share Alike 4.0 International license.